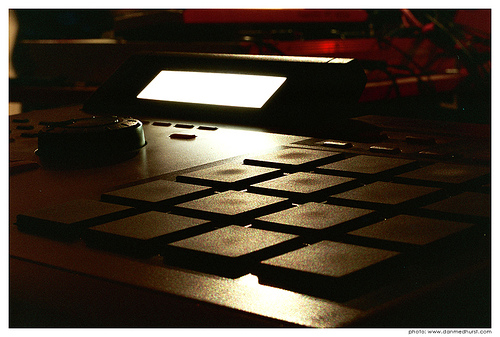

Akai MPC 2000 Photo Credit: Dan Medhurst

Welcome readers.

I hope this post finds you well. The topic of this post is something I’ve been meaning to write about for quite some time. Sampling has been a long time tool and methodology of music composition. I’m almost certain everyone reading this post is familiar, in some form or fashion, how sampling has found it’s way into modern day music creation.

While there are MANY articles and multimedia on this subject I’ll give a little background as a foundation to the reason why I’m writing this post – my own perspective on sampling: where it came from and and where it is today and some of my own opinion as a musician, songwriter, and producer. It’s not my intent to write about the chronological history of sampling (though I begin by citing its early days), but to talk about how I use and the reasons why, as I compose my own music. To give added perspective from others, I’ve also got a short interview with an artist on Twitter that uses sampling in her compositions, as well as an excerpt from an podcast I recorded, interviewing another artist on Twitter who is a sampled-based composer. You can check these out in future parts to this blog post.

Without going too far back to the first non-commercially available samplers, such as the Computer Music Melodian or EMS MUSYS, the first commercially available samplers actually came on the scene as the second wave of samplers. These are the more recognizable machines such as New England Digital’s Synclavier (’75), the Fairlight CMI (’79), and the Synclavier II (’80), While these samplers were to be found on many album liner credits, they cost in excess of $25,000 and obviously were only in reach of the top music superstars.

By the mid-80’s, the advent of sampling technology allowed for less expensive machines which were also smaller. Popular models of this era included the keyboard based Ensoniq Mirage and it’s rack version, the Mirage Rack, the Akai S612 (which used the least popular 2.8″ QuickDisks (same as some typewriters used), the Sequential Prophet 2000, the Akai S950, the Yamaha TX16W, and Roland S-550. These units boasted 12-bit sample resolution. You can hear the Mirage sampler usage all over Janet Jackson’s “Control” album, for example, the digital horn blasts on the hit “When I Think Of You”. I owned both the Yamaha TX16W and Roland S-550 samplers and participated in the Roland S-Group Sampler forum. Though the forum is pretty much non-existent these days, I still have a set of samples I uploaded to their archives in the late 90’s (ahh the good old days!). My primary use of the S-550 was to use snippets of samples I’ve created (mainly in the hip hop and dance genres) for use in my own compositions. Strangely enough, I never did any live sampling via a unit’s mic input, but instead used various Mac audio editing apps to convert audio to S-550 format.

It’s a well known fact that by the late 80’s, the E-mu SP1200 became the premier choice of samplers for commercial and indie hip-hop producers worldwide. Introduced in 1987, The grimy 12-bit sampling resolution and 10 second maximum sample time proved to have it’s limitations but despite that, it became the hallmark, signature sound of old-school hip-hop and house music. The SP-1200 was SO popular that it got reissued and manufactured through 1997. All the major hip-hop producers out of NYC, from Lord Finesse to Marley Marl to Pete Rock used the SP-1200 has their weapon of choice. Below is indie beat maker Surock showcasing a track done on the SP-1200.

In 1988, Roger Linn (known for the famous Linn Drum (think Prince tracks from Purple Rain), created partnership with Japanese corporation Akai and created what is probably singlehandedly known as the greatest machine made for creating hip-hop music: The Akai MPC Music Production center. Scores of hip-hop legends from DJ Premier to Pete Rock dominated this machine and made it the center of hip hop production. The MPC-60 began a long heritage of MPCs such as 2000, 2000xl, 3000, 2500, 1000, 4000, 5000, 1000 and 500. The MPC is known for its TIGHT timing and swing that is a staple of 90’s hip hop, still incorporating, as a 12-bit sampler, that grimy sound both associated with and loved in, hip hop. Here is a history of the MPC in video format:

Here is indie producer Disko Dave of The Better Beat Bureau on the MPC 2000 showing any of its capabilities in making a track (“beat”).

As a songwriter, musician, and composer, I grew up playing in R&B bands as a teenager. The drum machine found it’s way into my composition tool box way before an actual computer did. By this time, the same vendors that manufactured hardware samplers, also manufactured drum machines that had internal sounds based on PCM samples of various drum kits. I became, like many, accustomed to programming drum tracks on these machines which have pads just like the MPC. As my studio grew, it wasn’t until about two years ago that I finally got around to incorporating a MPC 1000 into my setup. What I enjoy about using the MPC is not only the availability to load and edit samples for tracks, but I much more enjoy programming drum tracks with pads via using a keyboard.

With the availability of the sampler in mainstream music production, it exploded in the area of hip-hop, with artists “crate diggin” for the most obscure tracks on vinyl to create the next banger. It turns out that the most sought after, used (and frankly exploited) tracks came from one artist, the hardest working man in show business: James Brown. To get an idea of just how much of his music was sampled in hip-hop (and beyond) check this link out. While the use of JB’s music greater exposed him to even music fans (young and old), there’s always been the issue of legality in sampling his tracks and tracks of the artists he produced. I’ll touch on legality issues in a subsequent part of this post. Suffice it say, I’ve heard some of the most ingenious and creative results of sampling Mr. Brown over time, some being the hottest tracks ever created. There is no question that James Brown and his music provided the fuel to propel hip-hop forward in many ways. Once again, barring the legal issues, the skill and creativity of hip-hop producers in the sampling of JB’s tracks, paid him great homage (and still do).

That’s it for now. In Part 2, I’ll give my thoughts on sampling vs interpolation and touch briefly (as if it hasn’t been touched on enough), the legalities of sampling.

Til then, peace…

F!

::thumbs up::

I still have somewhere, that issue of Keyboard Magazine which featured groove-meister Teddy Riley. He preferred to do his own live sampling, thinking instrument samples from vinyl just weren’t hard hitting enough.

http://audio.tutsplus.com/category/freebies/